By Greg Butterfield

By Greg Butterfield

Workers World, Published Sep 9, 2007

Attorney Charlotte Kates co-chairs the Middle East Subcommittee of the National Lawyers Guild. She’s also an organizer with Al-Awda NY and New Jersey Solidarity-Activists for the Liberation of Palestine.

In early August, Kates participated in a delegation to Palestine co-sponsored by Al-Awda and the Palestine Solidarity Group of Chicago, in conjunction with the Union of Palestinian Women’s Committees and other grassroots organizations. Workers World spoke with Kates about her experience.

Workers World: What was the purpose of the delegation?

Charlotte Kates: There was a strong focus on Palestinian political prisoners. Eight activists from a variety of backgrounds participated. Three were attorneys and there were others who work on political prisoner issues. Two delegates had worked in the Irish movement, including one currently living in Ireland who works with former IRA political prisoners.

We had several meetings with former political prisoners to find out what was happening inside Zionist jails. At the same time, we also met with activists in other spheres of life: youth organizers, women organizers, agricultural and labor activists. Almost universally, everyone we met with had spent some time in an Israeli jail or administrative detention.

Over 25 percent of all Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza since 1967 have spent time in Zionist jails, either as political prisoners or administrative detainees, which is a form of political imprisonment where they never have to present charges against you or classify why you’re being held and you never receive a trial.

We also learned that Palestinians who hold Israeli citizenship and live within the borders of Palestine 1948 are subject to similar repression.

There’s a myth that the Israeli regime has moved beyond torture, that the high court has forbidden it, so there is now a more enlightened policy. But the reality is that when one form of torture is specifically outlawed, the government moves on to other, psychological tactics, that leave no marks on the body but can be physically and psychologically damaging.

We heard time and again about the methods that were used in an attempt to break prisoners’ spirits: threats to family members, the use of stress positions, sleep deprivation, loud music, light. It’s very similar to what the U.S. has been reported to engage in at Guantánamo, Abu Ghraib and elsewhere.

One thing that was really amazing was that despite these horrible experiences universally shared by Palestinians under interrogation, they organized, spoke with their fellow prisoners, and once released, they continued organizing. The prison itself became a school for struggle.

WW: Were you able to meet with any current political prisoners?

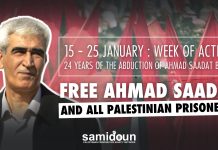

CK: We were not able to go into any of the jails. But on Aug. 8 the three of us who were attorneys were able to attend the trial of Palestinian national leader Ahmad Sa’adat at Ofer military facility outside Ramallah. This was arranged by Addameer, the Palestine prisoner support network.

Sa’adat is the general secretary of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. He was kidnapped by the Israeli army on March 14, 2006, after a 10-hour siege on a Palestinian Authority prison in Jericho. Sa’adat, four of his PFLP comrades and another prisoner were being held there under guard by U.S. and British forces.

Sa’adat was elected to succeed Abu Ali Mustafa, who was assassinated by an Israeli missile attack in 2001. Fighters from the PFLP’s military wing killed an extremist racist Israeli minister, Rehavam Ze’evi, in retaliation. From that time, the Zionist government had maintained that they sought to try Sa’adat for what they termed the murder of Ze’evi.

But after five years, Israel’s Ministry of Justice was forced to admit there was no evidence to pursue the charge. Instead they came up with 19 charges against Sa’adat which are very political in nature—things like being a member of a banned organization, holding a post in an illegal organization, and incitement for making a speech after Mustafa’s assassination.

The trial has been postponed numerous times. The prosecution has a list of 39 witnesses. These are political prisoners who are put on the stand and don’t have anything to say. They don’t even know they’re being taken to Sa’adat’s trial. They’re taken out of their cells at 2 o’clock in the morning, put in a van, taken to Ofer and brought into the courtroom.

The prosecutors start barking at them and try to get some kind of incriminating statement by asking questions like, “How did you meet Sa’adat?” and “What is his position?” One witness said he knew who Sa’adat was because he’d seen him on the news.

Three military judges were seated at the front of the room and barked out when they heard people translating the proceedings in the back, telling them to be quiet. At the end of the hearing, one judge said to a prosecutor, in a very buddy-buddy tone, “Why are you bringing all these witnesses? We don’t need them.” The implication was clear: they’ve already made up their minds.

While we observed this hearing, Sa’adat was seated in a box to our right. His feet were shackled. He would pay attention to the proceedings only when another Palestinian prisoner was on the stand.

Sa’adat has maintained throughout that he absolutely refuses to recognize the legitimacy of these courts. He refuses to stand for the judge. His attorneys observe and compile very detailed notes, but they will not participate in what is at its core an illegitimate process with no authority to pass judgment on Sa’adat or any other Palestinian.

WW: Did you see a connection between Palestinian prisoners and political prisoners held by the U.S.?

CK: Right now, the U.S. maintains a military prison at Guantánamo Bay on the basis of secret hearings devoid of any real process. The so-called war on terror has been the justification for holding hundreds of men there, in addition to thousands of people being held in Afghanistan, Iraq and secret CIA detention around the world.

Much as the Israeli military courts are illegitimate forces of occupation, we see the same thing at Guantánamo, which is occupied Cuban territory. It’s a prison camp for the international political prisoners of the U.S.

Increasingly we hear Guantánamo called a stain on U.S. history. But political imprisonment is nothing new here. There are many political prisoners, from Mumia Abu-Jamal and other veterans of the Black Liberation Movement to the Puerto Rican Liberation Movement and other struggles for social justice. It’s certainly nothing new for U.S. proxy regimes like Israel.

Every day U.S. taxpayers are spending between $10 and $15 million to support the Israeli state. We’re paying for the trial of Ahmad Sa’adat. We’re paying for the detention and imprisonment of 11,000 Palestinian political prisoners, just like we’re paying for the detention of thousands of Iraqis and the ongoing abuse of hundreds of men at Guantánamo. The torture is the same, the abuse is the same, and the injustice is the same.

We must confront head-on the responsibility the U.S. has for the political imprisonment it’s engaging in and supporting and paying for around the world.

There’s an international campaign to free Ahmad Sa’adat and all Palestinian political prisoners. Sa’adat’s trial has been postponed again and is scheduled to reconvene on Nov. 4. The campaign is asking people to get involved, hold events, send letters and write statements to raise awareness about his case. Please visit www.freeahmadsaadat.org or email campaign@freeahmadsaadat.org for information.

To host a speaker from our delegation, please contact info@al-awdany.org.

Articles copyright 1995-2007 Workers World. Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved.